Gabriel García Márquez: Seeing the boom in Mexico |Confabulary |Cultural supplement

Gabriel García Márquez: Seeing the boom in Mexico

Dec 18 • We highlight, main, reflections • 9696 views • No comments in Gabriel García Márquez: Seeing the boom in Mexico

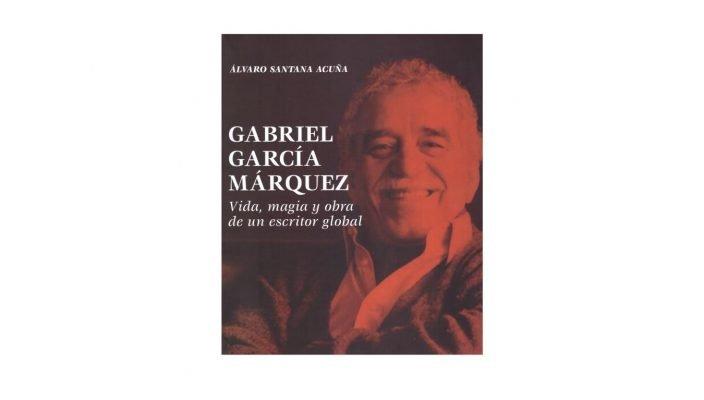

TweetGabriel García Márquez arrived in Mexico in 1961 determined to succeed in the cinema as a screenwriter, but the success of a hundred years of solitude in 1967 showed him his destiny.With the authorization of the editorial the balancer, we reproduce this fragment of Gabriel García Márquez.Life, magic and work of a global writer, by the historian Álvaro Santana Acuña, revealing book that, from the personal archive of the Nobel, reconstructs the life and work of the narrator, with documents and rare and unpublished images

By Álvaro Santana Acuña

The great boom of the Latin American novel came when we managed to conquer our readers readers in our own countries.García Márquez

With suitcases full of illusions and his two -year -old son, Gabo and Mercedes entered an unknown country where immigrants were again.The capital, Mexico City, was its new house and also that of almost five million people.This millenary metropolis lived a rapid economic modernization that also made its cultural industry flourish.The cinema especially enjoyed twenty years of its “golden age”, with famous films starring Pedro Infante, María Félix, Jorge Negrete, Dolores del Río and Cantinflas, among other unforgettable faces that traveled through the screens of Latin America andSpain.

García Márquez landed in Mexico City looking for the golden Mexican cinema.What I did not know is that the city was going to be transformed soon, like Buenos Aires and Barcelona, in one of the capitals of the "new Latin American novel".This literary movement reached such a sudden and vertiginous international success that began to talk about a boom of Latin American literature.At first, García Márquez was just an accidental witness of the boom, but in a few years he would become one of his best known writers thanks to the success of a hundred years of solitude.However, at the end of June 1961, when he arrived with his family in Mexico City, he could not imagine that a novel of his reached fame.

The newcomers were received by the unconditional friend and Colombian poet Álvaro Mutis, who resided in the capital since 1956.It was Mutis who was presenting his friend to important Mexican artists.Gabo did not take long to demonstrate his literary talent and impress his new colleagues and readers.A few days after arriving, he learned that his admired Ernest Hemingway had just died and decided to honor him by writing the article “A man has dead natural death”, which appeared in the well -known Mexico supplement in culture in culture.The title of his tribute turned out to be a paradox because, at that time, it was not said that Hemingway had hit his favorite shotgun.The good reception that had his article allowed him to meet "the cream of intellectuality," as Gabo told his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza.But, as he wrote to another friend, Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, he had not emigrated to Mexico City to write only literature, much less do journalism, but dreamed of working in the powerful Mexican film industry.Although things that revolted their plans began to happen.

When he discovered his new country, Gabo met an ancestral culture that gave him inspiration for his stories.In a letter to Plinio in August 1961, he told him that during a visit in a town in Michoacán he had seen “the Indians weaving angels of straw, to whom they put shoes and dresses in the region”.Right there, he explained, the idea of writing “a very old man with huge wings” had occurred to him, a story in which the people of a village visit a winged being of an advanced age.Gabo added in his letter, "I have the batteries loaded to launch my old project of the Fantastic Tales Book" that occur in a poor town where the carpets fly.

Thanks to these discoveries, Gabo began to feel that the events of Mexican daily life that witnessed, where the magical and real mixed in ways he had never seen, were encouraging him to resume the project that many ideas, stories and stories andcharacters for his novel one hundred years of loneliness and the book of stories The incredible and sad story of the candid Eréndira and his heartless grandmother.Gabo was not the only one who had felt the inspiring call for Mexican magical realism.It happened to Juan Rulfo, the author of Pedro Páramo, whom Gabo met in those years and that influenced him in his future works.Something similar happened to Mexican photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo and the Spanish-Mexican director Luis Buñuel, with whom García Márquez was going to carry out film projects.

At first Gabo did not have it easy to enter the world of Mexican cinema and less being an immigrant without papers.First, I had to find an employer to sponsored your work visa.That opportunity came thanks to producer Gustavo Alatriste.Although he did not want Gabo for the cinema but to direct two magazines that he had just bought, events for all and the family.Gabo would be responsible for modernizing and increasing the sales of both.His dream of making movies had to wait.

Events for all, with a weekly circulation of more than fifty thousand copies, highlighted among the best -selling magazines in Mexico.At that time, it was still expensive to have a radio or a TV at home, while the copy of a magazine read several people.Therefore, events for all were also among the most read in the country.Designed to reach as many audience as possible, the magazine offered striking images and curious texts of easy reading about news.In addition, Gabo added contents about art and literature, publishing for several months a selection of stories of the thousand and one nights, the classic of Arab literature that influenced so much on a hundred years of solitude.

The other magazine that Gabo directed, the family, was designed for middle -class housewives.In its pages, he put the “sentimental literature” section, which appeared between cooking recipes, sewing patterns and advertisements of miraculous appliances.Under his direction, this magazine also grew and even published an international edition for the Latin American market outside Mexico.

García Márquez said that his work was easy, he left him time to write and earned a good salary.After years of penalties and deprivations, I was now living a bourgeois and comfort life.In addition, his family grew in 1962 with the arrival of the second son: Gonzalo.But the creative Gabo was not happy.His position seemed to him the lowest class of journalism he had made.For that reason, he asked that his name not appear in any of the magazines, although he supervised everything, from the creation of content to the review of the copies fresh from the printing press.However, his activity in these magazines ended up being a very important professional experience, because, being forced to raise sales, he had to understand the cultural tastes of his readers: the urban middle classes of Mexico and Latin America.These readers were going to become the main buyers of the Latin American boom novels in those years.What Gabo learned in events for all and the family served to reach this reading audience that devoured one hundred years of loneliness.

Gabriel García Márquez in a cameo in this town there are no thieves, accompanied by actor Julián Pastor.Editorial The Balancer

Thanks to his good work with the magazines, García Márquez won the confidence of Chief Alatriste, who already thought of him for major projects.His boss was a successful film producer.He had financed two films from Buñuel, Viridiana and the exterminating angel, who received several awards at the Cannes Film Festival in 1961 and 1962, and who also won the enthusiasm of critics and the favor of the public of the public.In 1963, Alatriste told Gabo to leave the address of the magazines and offered him the work of his dreams: writing full -time film scripts.Gabo exceeded happiness.Finally, after years of sacrifice, he had fulfilled his desire to be "professional writer", as a friend told.To another he told him, “everything is doing very well.I live exclusively from my golden dream: I write for cinema ".It was then that he began to collaborate in the scripts with a person who was key in his career: Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes.

Gabo and Fuentes had met years before, when the Mexican invited him to participate in the activities of "La Mafia".With this affectionate name he called himself a group of artists residing in Mexico City.In addition to Fuentes, the leader, to “La Mafia” belonged by the writers José Emilio Pacheco, Juan Vicente Melo, Juan García Ponce, Emilio García Riera, Elena Garro, the directors Buñuel, Arturo Ripstein and Alberto Isaac, the actress Rita Macedo and theLiterary critic Emmanuel Carballo.The group used to celebrate parties to entertain foreign visitors, such as American actor John Gavin, British artist Leonora Carrington and Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier.

Joining "La Mafia" marked a before and after in Gabo's professional life, who often could talk with influential people from the world of culture.He told them about his past, present and future novels, while his colleagues told him something they presented: it was the moment of Latin American arts, especially literature.

Several of the "mafia" colleagues helped García Márquez with their friendship, their money and their ideas during the writing of one hundred years of solitude.Fuentes was among them.His friendship was forged thanks to long hours dialoguing on literature while adapting to the cinema El Goldo de Rulfo and also an original Gabo script entitled El Charro, which was going to be like a film from the old west set in Mexico in Mexico.In addition, thanks to the cinema, Gabo made two friends for a lifetime, director Jomí García Ascot and actress María Luisa Elío, creators of a movie that marked him, on the empty balcony, about an adult woman who recalls a sad oneEpisode of your childhood.

The cinema wind blew so in his favor that García Márquez looked even working in Hollywood, as a friend told.But suddenly the wind changed direction and stopped him dry.Alatriste informed him that he was not going to pay him more for his scripts because he had problems to finance his films.He only committed to Gabo to keep him the job visa.Back to the address of the magazines was not possible either, so another job had to be sought.The best thing he found, a sad and disoriented García Márquez who dreamed with Hollywood, was a position from eight in the morning to five in the afternoon at an advertising agency.It was not a bad job, although Gabo believed that he was moving away from his goal of being a professional writer.Actually, he was not (nor was it going to be) the only Latin American writer who found a temporary lifeguard in advertising.For example, Rulfo and Carpentier also survived with advertising orders.

As with the magazines, García Márquez was not proud to be a publicist, but in the long run, that new work was going to reward him with unexpected creative benefits.Thanks to advertising, he learned novel marketing strategies, which he later used to promote his literary works and thus reach larger audiences.As in the magazines, he never signed with his name the work as a publicist, so it is difficult to follow the trail.One of its advertising texts, commissioned by a chemical company, is called 5000 years of Celanese Mexicana.In its pages, the mixture of advertising and literary techniques becomes only one thing.And both the title and the narrative style of this text without its signature resemble the title and the prose of one hundred years of solitude.

The poet Jomí García Ascot with Gabriel García Márquez and Mercedes Barcha, Circa 1967, photographed by María Luisa Elío, wife of García Ascot. Editorial The Balancer

The publicist Gabo did not give up making cinema and, to achieve it, he contacted the famous Mexican producer Manuel Barbachano.Since then and for more than a year, Gabo was a day publicist and freelance screenwriter for the afternoons and nights after work.His effort obtained reward.In 1965, there were no thieves in this town, which was the film adaptation of a story about a robbery in a town they falsely accuse a man.In the film acts by García Márquez himself, who is the collector at the entrance of the movie theater.Several of his friends of "La Mafia" also participate: Buñuel acts as a cure giving a sermon and Carrington is among those who listen to him, Rulfo and Carlos Monsiváis play dominoes, Luis Vicens is the owner of a room, García Riera is an expert in billiards...

At that time, Gabo was also developing, with the help of a scriptwriter from Buñuel, Luis Alcoriza, an idea of his for a movie: omen.It tells the story of a remote people where a midwife has the premonition that something terrible will happen.And the script of El Charro, Gabo's great film project, became time to die.In the film, the protagonist, Juan Sáyago, returns after eighteen years in jail to his people, where the children of the man who killed waiting for him to take revenge and kill him.This film was also Gabo's first project with Mexican director Arturo Ripstein, who years later filmed an adaptation of the Colonel does not have who writes to him.

Time to die was filmed in June 1965, when the dream of cinema was gathering strength for Garcia Márquez.A photo taken in Acapulco that summer shows it surrounded by a select group of cinema people.He was accompanied by critics, directors, actors, producers and screenwriters, such as Isaac, Buñuel, Alcoriza and Ripstein.Gabo was clear.His future was in the cinema.Literature was the past.As a friend confessed, “Imagine that I am now charging ten thousand pesos to check a script.And think that I have lost so long of my life writing stories and reports.In addition, everything in literature seems to be written ".And then Gabo sentenced, "literature is fabulous to enjoy as a reader ... not as a writer".

But when it seemed that García Márquez's career was going to be in the cinema and that literature would lose it forever passed an extraordinary fact: the Latin American boom storm unleashed.Around 1962 a fine rain of novels written by authors of several generations had begun: that of Carpentier and Miguel Ángel Asturias, Mario Benedetti and Ernesto Sábato and José Donoso and Fuentes.Almost ignored books for years, such as fictions by Jorge Luis Borges and Adam Buenosayres by Leopoldo Marechal, they became supervants of the moment.The new books, such as the city and the dogs of Mario Vargas Llosa, bomarzo of Manuel Mujica Láinez, Rayuela de Julio Cortázar and the shipyard of Juan Carlos Onetti.

Around him, Gabo listened to in amazement the news about the commercial success of his friends writers.Soon, the boom rain began to wet him.The editors sought to publish Latin America literature and, for the first time in their career, Gabo accumulated the opportunities to reimpress his previous works, so little successful until then.In 1961, after almost four years of waiting, the Colombian publishing house Aguirre published the first edition of El Colonel has no one to write.In 1962, the Veracruz Universidad de México launched the funerals of the big mother, its first book of stories.That same year, his novel The bad hour won the Esso prize for the best Colombian novel, receiving the sum of three thousand dollars and the publication of the work in Spain.In 1963, the Mexican publishing house was printed a new edition of El Colonel has no one to write.That year Gabo signed the contract to get this novel with René Juliard, a small but prestigious French editorial who published avant -garde writers such as Louis Aragon, Italo Calvino and Vladimir Nabokov.That was his first book translated.

The García Barcha marriage dancing in Puerto Colombia, 1971.Armando Matiz/ Taken from the book Gabo Journalist, by Gabriel García Márquez (FNPI, 2012).We thank Editorial the balancer

But publishing more did not mean being better known.Before one hundred years of solitude, García Márquez's works were only well received by small circles of writers, critics and readers in Mexico and Colombia.Their books had taken them local publishers who offered him contracts plagued with abusive conditions.The runs were small and rarely passed from the two thousand copies.In addition, the distribution was slow and local.For example, two years had to spend copies of the Mexican edition of El Colonel has no one to write to sale in the Libraries of Uruguay.Often the fastest method for his books to cross borders was that Gabo himself gave them to friends.

The best possible news to sell many copies was to receive an award and create a scandal.This happened to the bad hour after winning the ESSO award.The novel was printed in Madrid, where a style concealer modified without permission the Spanish Colombian of García Márquez so that the readers read it as if they were written in Spanish of Spain.The writer complained with forcefulness and the controversy reached the Spanish media.The ABC newspaper reported that the publishing house admitted the error and offered the author to withdraw the edition and print a new one with the original text.For its part, the Spanish Government Censorship Office said it had nothing to see with the manipulation of the text.

In the end, García Márquez made a public statement with a peaceful tone, saying that he trusted that “in the future all Latin American writers will be treated as adult by Spanish editors”.Gabo was right because then it was a common practice that the manuscripts of Latin American authors were subjected to linguistic censorship.It happened to Carpentier, Fuentes, Vargas Llosa, Donoso, Cortázar, Guillermo Cabrera Infante and other less and better known writers in boom.But almost all were willing to run that risk, because publishing their book in Spain - the center of the book industry in Spanish - was a great step forward for many Latin Americans who aspired to be professional writers.

In 1964, the drizzle of the Boom had become a flood of new works and new names that received the firm support of great publishers such as Knopf in the United States, Gallimard in France, Feltrinelli in Italy and Seix Barral in Spain in Spain.Critics also greeted Latin American novels from Le Monde's pages in France, The Times Literary Supplement in the United Kingdom and Life Magazine in the United States.But above all it was the Latin American publishers and criticism that most approached the public to Latin American writers, who now appeared on the cover of magazines and newspapers such as the great stars of the moment and, in the interior pages, their works were praised like whatbetter that had been published in the region.This was done by myth magazines in Colombia, first flat in Argentina, culture in Mexico, marches in Uruguay, literary role in Venezuela, Casa de las Américas in Cuba, Amaru in Peru, Ercilla in Chile and, above all, new world inParis.It was even rumored that Borges was going to win the Nobel Prize for Literature at any time, while he, increasing.Something had changed: Latin American readers were discovering their own authors.

García Márquez, amazed, knew about the triumphant reality of Latin American literature thanks to the conversations with his friends of "La Mafia", especially with Fuentes.In 1964, he published an essay destined to make history: "The new Latin American novel".With that name, he was the first to baptize this literary movement and celebrated that the novels of Carpentier, Cortázar and Vargas Llosa were changing the course of the literature of the region.Fuentes himself knew what he was writing, because he was already a famous writer whose books were sold in a dozen countries.Soon, his essay became an artistic manifesto, read, shared and supported by other authors and critics such as the Uruguayan Ángel RamBoom of the Latin American novel.

Seeing the closest success, García Márquez began to feel full.In a letter from 1964, he told Plinio that it was the time of the new Latin American novel and that finally Latin American writers "now we have guts".It is true that he still had doubts about his future as a writer, but that changed in Mexico in the summer of 1965.When the young Chilean writer and critic Luis Harss.He told him that he came to interview him for a book of conversations with ten Latin American writers, Carpentier, Asturias, Borges, Onetti, Cortázar, Rulfo, Fuentes, Vargas Llosa and João Guimarães Rosa.García Márquez was another of his chosen.But unlike the other nine, he was the least known and published at that time. Semanas después de la entrevista, las dos editoriales que iban a sacar el libro de Harss, Sudamericana en Argentina y Harper & Row en los Estados Unidos, estaban negociando con Gabo para publicar su próxima novela, Cien años de soledad.Harsss's book was launched almost at the same time in English with the title into the mainstream and in Spanish with that of ours.The book was an instant supervent in Argentina.In this and other thousands of Latin American readers they discovered in the pages of ours that Latin America literature was in full boom.

Days after the meeting with Harss, García Márquez received the visit of another person who was going to have a decisive force in his career and in the success of the boom: the Catalan literary agent Carmen Balcells.Since 1962, she was negotiating the sale of the translation rights of Gabo's stories and novels.In the summer of 1965, Balcells traveled to Mexico City to get new contracts, clients and publishers.García Márquez offered to sign a much more ambitious contract to represent him in all languages and in the world.With that document in his hand, there was no reversal: García Márquez was finally a professional writer.

Also, on a brilliant day of that prophetic summer of coincidences and certainties, Gabo said that he was driving from Mexico City Acapulco to enjoy a vacation with Mercedes, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, when they suddenly crossed a cow in the middle of the highway.At that precise moment, after stopping the car, Gabo came up with the first sentence of a novel he had wanted to tell for fifteen years.Then he did not hesitate.According to him, he decided to go back and immediate.

Photo: Cover of the book Gabriel García Márquez.Life, magic and work of a global/ credit writer: the balancer and foundation for Mexican letters

Boomcien years of solitude in this town there are no thievesgabriel García MárquezSucesos for all

«Jorge Ayala Blanco: Mexican and international cinema in 2021 the prose of life»

New Balance shoes: from "no one endorses them" to becoming the new favorite shoe of some sports stars

05/02/2022This is the video transcript.Fabiana Buontempo: What do tennis star Coco Gauff, NBA MVP Kawhi Leonard, and Liverpool footballer Sadio Mané have in common? They all use...